The June 23, 1988 issue of EDN included a Maxim Design News insert where we asked "Who in their right mind would choose a computer interface standard that uses ±12 V supplies, requires expensive connectors, works over a limited distance, is error prone, difficult to network, and has no current loop isolation?" Yet, here we are 28 years later and the classic interface lives on, particularly in industrial applications and applications that need to connect just one peripheral to a host computer.

First sold in February 1988, the MAX232 skillfully married two seemingly unrelated functions, power and interface, and marked the beginning of a different way of thinking about what "analog" ICs can do. That thinking has taken on an even larger and more complex scale with the mixed-signal devices we see today.

The MAX232's success was as much a tribute to the vision of its definer, Charlie Allen, as it was to the ingenuity of its designer, Dave Bingham. Before the MAX232, RS-232 interfaces consisted of two chips, a 1488 quad line driver and a 1489 quad line receiver (both 14-pin DIPs), along with a bipolar ±12 V power supply. In most systems leading up to that point, the common voltages used in hardware were +5 V for logic and ±12 V for analog. Because ±12 V was already generated for other parts of the system, tapping them for the serial interface drivers was not an inconvenience.

By the 1980s, however, more and more hardware, including analog functions, could be powered from a single 5 V rail, both because more of the system became digital and because the analog circuitry they did have could now be built with newer analog ICs that could operate from 5 V, making ±12 V less necessary. In fact, Maxim and its peers hastened this shift by developing high-performance 5 V-powered analog ICs such as single-supply op-amps, data converters, and analog switches.

Recognizing this trend was key to the birth of the MAX232. It became clear from that vantage point that it would not be long before the RS-232 interface ended up as the last function in the system to need a bipolar supply. It would effectively be the "high nail" that had to be hammered down.

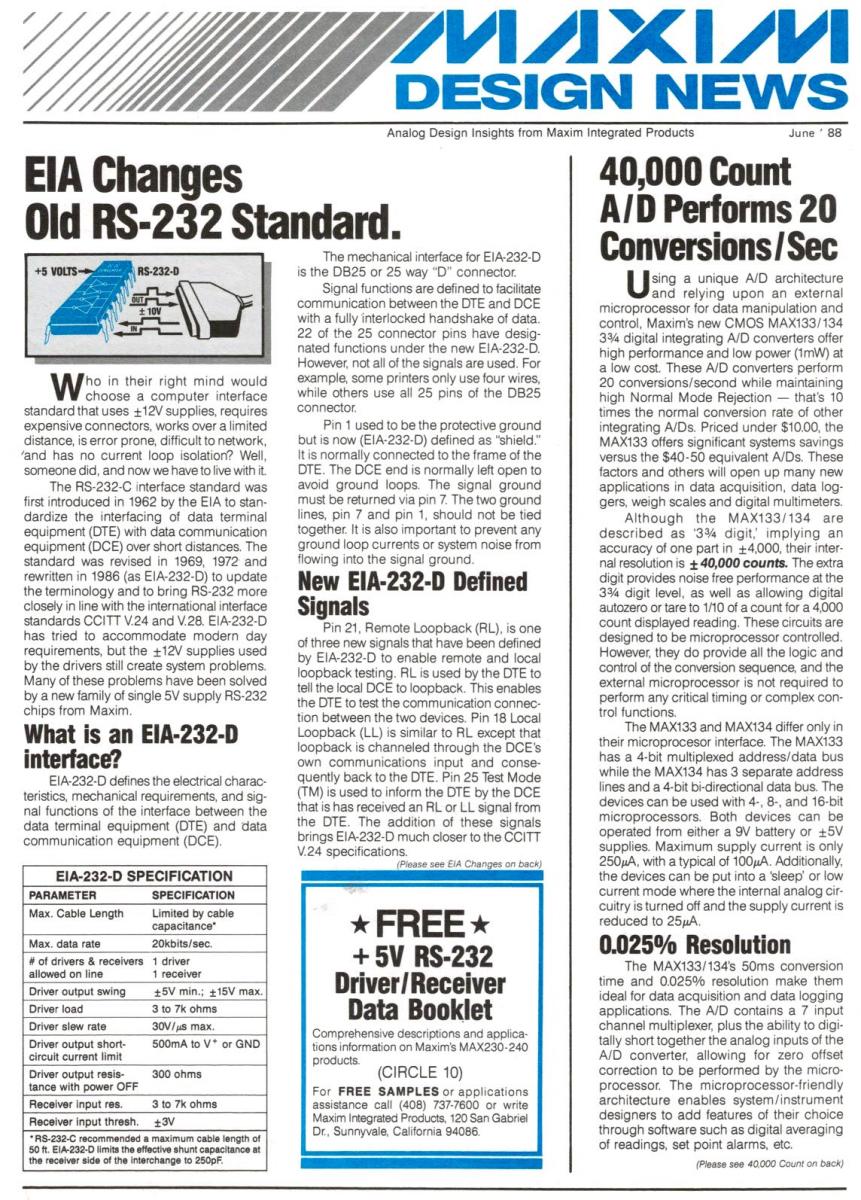

After the "eureka" point was reached and the need was clear, there was still the challenge of how to both develop +10 V and –10 V rails from +5 V and then produce that on the same silicon as the line drivers and receivers. DC-DC converter chips were not new at the time, but their circuits were complex and needed inductors, which Maxim knew its customers wanted to avoid.

Another less-used type of power-supply circuit was the charge pump, which had the benefit of not needing an inductor. A popular device at the time was the ICL7660, but it could only invert a positive voltage or, with a different connection, double an input voltage. The new line driver needed to both invert and double at the same time, a more complex order than simply combining two circuits because the negative output complicated biasing the substrate. In addition, the line driver and receiver output and inputs had to connect to the outside world, and as such, had to have robust ESD protection. In that regard, the MAX232 was almost like an Apollo ("man on the moon") program for CMOS ESD protection, driving ESD advances that still benefit ICs today.

At the IC design level, the concept of combining functions with their power supply was also nonexistent. In the 1980s, analog was predominantly a bipolar IC process world. CMOS existed for logic but the best op-amps and voltage regulators were still built on bipolar processes. Not much analog performance was expected from CMOS in the 1980s. It took Intersil (also founded by Maxim's founder, Jack Gifford), to begin convincing people that CMOS could do heavy lifting in analog circles, but not yet with power. It took a second generation of CMOS design, at Maxim, to move that forward with the MAX232.

Like many innovations in history, at the time the MAX232 was announced, no one was asking for such a device. Combining a digital function with power was not something engineers thought about. The MAX232 development required system-level thinking from an IC company, something that was far from the norm. At that time, analog IC companies’ technical interaction with customers consisted of helping them select op-amps, voltage regulators, ADCs, etc. based on customer specs, and trouble-shooting customer problems. Not much time was spent on the "big picture" and the larger view of customer problems and goals. The MAX232 led the change away from treating analog functions as individual blocks in an effort to develop parts that were easier for customers to use. For analog (really all mixed-signal) companies today, that once-novel approach is now mandatory.

没有评论:

发表评论